Over time, the stock market’s returns come from two key components: investment return and speculative return. As Vanguard founder John Bogle has pointed out, the investment return is the appreciation of a stock because of its dividend yield and subsequent earnings growth, whereas the speculative return comes from the impact of changes in the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio

Price Multiples

A. Price-to-Sales (P/S)

P/S ratio = current price of the stock / sales per share

The good thing about P/S ratio is that sales are typically cleaner than reported earnings because companies that use accounting tricks usually seek to boost earnings. In addition, sales are not as volatile as earnings. Thus, P/S ratio useful for quickly valuing companies with highly variable earnings, by comparing the current P/S ratio with historical P/S ratios. Also the P/S ratio can be used when earnings are negative (P/E ratios cannot be calculated – indicated as N/A).

Biggest flaw: Sales may worth a little or a lot, depending on a company profitability. A company may post billions in sales, but still losing money.

B. Price-to-Book (P/B)

P/B ratio = stock’s market value / book value (also known as shareholder’s equity or net worth).

The main weakness for P/B is that there is increasing trend in intangible assets worth, which may limit the usefulness of P/B ratio. For service firms which depends on brand, dedicated employees, strong customer relationship, efficient internal process, P/B has little meaning.

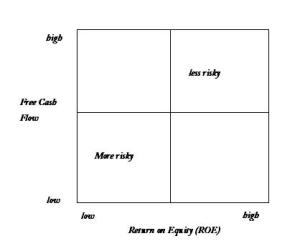

P/B is tied to ROE (equal to net income / book value), in the same way that P/S is tied to net margin (equal to net income / sales). Given two companies that are otherwise equal, the one with a higher ROE will have a higher P/B ratio. Therefore, when you are looking at P/B, make sure you relate it to ROE. A firm with a low P/B relative to its peers or to the market and a high ROE might be a potential bargain, but you’ll want to do some digging before making that assessment based solely on the P/B.

P/B is useful for valuing financial services firms because most financial firms have considerable liquid assets on their balance sheets. Financial firms trading below book value (a P/B lower than 1.0) are often experiencing some kind of trouble.

C. Price-to-Earnings (P/E)

The Good: accounting earnings are a much better proxy for cash flow than sales, and they’re more up-to-date than book value. Moreover, it is readily available.

The easiest way to use a P/E ratio is to compare it to a benchmark, such as another company in the same industry, the entire market, or the same company at a different point in time.

The Bad: Relative P/E has one drawback, a P/E of 12, for example, is neither good nor bad in a vacuum. Using P/E ratios only on relative basis means that your analysis can be skewed by the benchmark you’re using.

Risk, growth, and capital needs are all fundamental determinants of a stock’s P/E ratio:

- higher growth firms should have higher P/E ratios,

- higher risk firms should have lower P/E ratios,

- and firms with higher capital needs should have lower P/E ratios.

When you’re using the P/E ratio, remember that firms with an abundance of free cash flow are likely to have low reinvestment needs, which means higher P/E. Also:

- If a firm has recently sold off a business or perhaps a stake in another firm, it’s going to have an artificially inflated E, and thus lower P/E.

- If a firm is restructuring or closing down plants, earnings could be artificially depressed, which would push the P/E up. For valuation purposes, it’s useful to add back the charge to get a sense of the firm’s normalized P/E.

- If the firm cyclical? Firms that go through boom and bust cycles – semiconductor companies and auto manufacturers are good examples – require a bit more care. Your best bet is to look at the most recent cyclical peak, make a judgment whether the next peak is likely to be lower or higher than the last one, and calculate a P/E based on the current price relative to what you think earnings per share will be at the next peak.

- Does the firm capitalize or expense its cash-flow generating assets? A firm that makes money by building factories and making products gets to spread the expense of those factories over many years by depreciating them bit by bit. On the other hand, a firm that makes money by inventing new products like drug, has to expense all of its spending on R&D every year. Arguably, it’s that spending on R&D that’s really create value for shareholders. Thus, the firm that expenses assets will have lower earnings – and therefore a higher P/E – in any given year than a firm that capitalizes assets.

- Which type of P/E? There are two kinds of P/Es-a trailing P/E, which uses the past four quarters’ worth of earnings to calculate the ratio, and a forward P/E, which uses analysts’ estimates of next year earnings to calculate ratio. In general, forward P/E < trailing P/E. Forward P/E also tend to be too optimistic.

D. Price-to-Earnings Growth (PEG)

PEG = P/E divided by its growth rate

The problem with this measure is that risk and growth often go hand in glove – fast-growing firms tend to be riskier than average. This conflation of risk and growth is why the PEG is so frequently misused. When you use a PEG ratio, you’re assuming that all growth is equal, generated with the same amount of capital and the same amount of risk.

Don’t just pluck your money to the one with the lower PEG ratio, look at the capital that needs to be invested to generate the expected growth, as well as the likelihood that those expectations will actually materialize.

E. Yield is good

earning yield = 1 / (P/E), or earning per share divided by its market price.

The nice thing about yield, as opposed to P/Es, is that we can compare them with alternative investments, such as bonds, to see what kind of a return we can expect from each investment.

The best yield-based valuation measure is cash return. Cash return = Free Cash Flow / Enterprise Value (Enterprise value is simply a stock’s market capitalization + its long term debt – its cash). The goal of the cash return is to measure how efficiently the business is using its capital – both equity and debt – to generate free cash flow.

Essentially, cash return tells you how much free cash flow a company generates as a percentage of how much it would cost an investor to buy the whole company, including the debt burden.

BEWARE: Cash flow isn’t terribly meaningful for banks and other firms that earn money via their balance sheets.